Climate change impacts on fisheries

As species shift poleward to keep pace with climate change, they move away from those fishing communities that have relied upon them for generations, and become newly available to others. Fisheries are on the frontlines of climate impacts and their livelihoods are at stake. I testified to the House Subcommittee on Water Oceans and Wildlife on May 1, 2019 on the effects of climate change on fisheries and the need to design our management to be proactive.

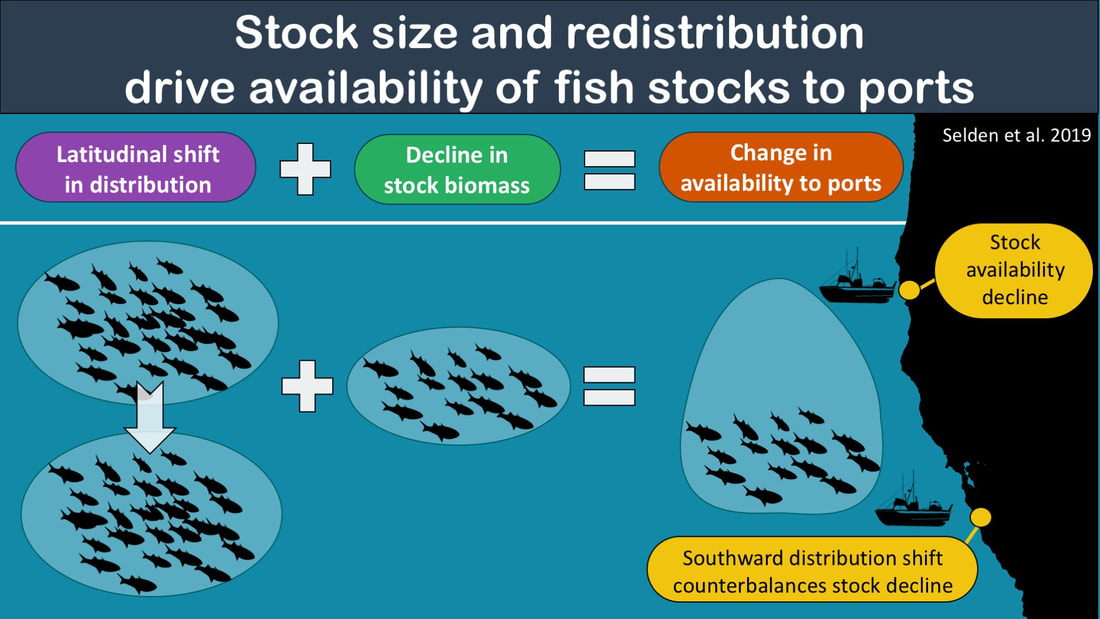

Our paper in ICES Journal of Marine Science describes how changes in overall stock biomass interact with shifts in species distributions to result in dramatic differences in availability to fishing ports along the West Coast.

Warming effects on marine ecosystems |

As suitable thermal habitat moves poleward, marine species are shifting their spatial distributions. However, asymmetries in thermal responses among species may lead to mismatches in their response to warming and disruptions in key species interactions. My post-doctoral research at Rutgers University revealed that warming is driving range contraction among cold-water predators like cod in the Northeast US LME (a hot-spot of warming over the last ten years as shown in the map) and this is creating spatial refugia for its prey. In contrast, range expansion by predators with warmer-water affinity like spiny dogfish is leading to increases in spatial overlap with prey that may compensate for the loss of cod's functional role.

See paper in Global Change Biology

See paper in Global Change Biology

Image Credit: http://www.seascapemodeling.org/

Fishing alters marine food webs

Image Credit: Ray Troll

Image Credit: Ray Troll

While seafood can be one of the most sustainable forms of human protein, human harvest of large amounts of fish biomass has the potential to alter marine food webs, especially if predators are selectively targeted. Recent research has shown that over-exploitation of predators can drive trophic cascades in coastal and pelagic marine ecosystems. My PhD research examined whether fishing-induced reductions in predator size structure might drive similar ecosystem consequences even without dramatic reductions in predator abundance.

Size truncation alters potential for top-down control of sheephead on urchins Proc Roy Soc B

Diet changes with size drive impacts of fishing on predator-prey interactions Fisheries Research

Observe our predation experiments in action at Catalina Island